Recently, a writer friend of mine has had quite a bit of intermediate success. That seems like a mouthful, and it is. Her book is yet to be published; however, in the last few months, she’s had an agent requesting information from her, had a publisher approach her about a “secret project,” and also been accepted into an exclusive mentoring program where published authors assist their protégé in becoming the best writers they can be. In talking to her and another good writer friend of mine, we discovered that everyone has an opinion about what we write, good or bad.

This brings up the topic of critique: how to accept compliments with grace and how to interpret criticism without becoming personally emotional. Many writers feel that their work is their “baby,” and rightfully so. It is a labor of love that we writers pour our souls into. When (and if) we dare to let others read our work, we usually want honest reactions in our heads, but our hearts tell a different story. Receiving negative feedback feels akin to loosing ones puppy to a streetcar accident. Fortunately, writers have one advantage over this issue; our work is neither a baby nor a puppy. In fact, I propose that it is something both more intriguingly important and yet less significant.

Our “brilliant work of staggering genius” is, in the end, just one work of art, whether it’s a poem, painting, or the most intricate purple prose. The amazing thing about creating art is that the act is limitless in terms of imaginative potential. Or to put it more bluntly, you can always start over. In contrast, there will only ever be one puppy like yours and only ever one child like yours. Those are unique and worth fighting for. Art, on the other hand, is something of a different matter. You can always make another.

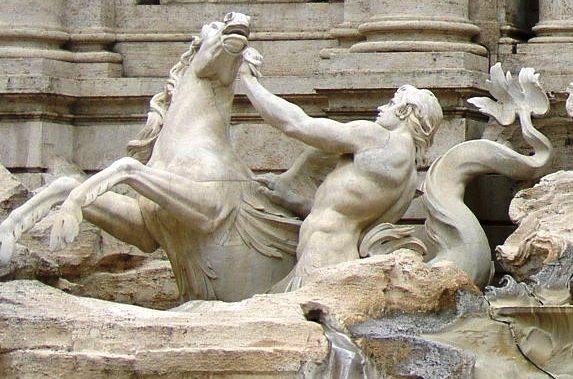

So, how does one accept criticism? The answer is with a great deal of patience and understanding. Let us say, for example, that you’ve just received an email from a “friend” who graciously agreed to read through your story and offer her suggestions. You anxiously click the email and open the attachment. Eyes scanning quickly, you spot red marks all over the page. It looks like the scene of a bloody battle. Once the initial shock of the gore wears off, you start to scan your friend’s hints with a wary eye. The natural response is to become defensive. That’s OK. Let yourself feel that emotion, but only for five seconds. Count: 1... 2... 3... 4... 5...

*whew* Feel any better? OK, maybe not yet, but we’ll get there.

Now, take a close look at the critique. Don’t worry about responding yet. Just scan what she wrote. Read through and get the overall impression. Now, let that sink in for a moment. Remember, this friend just took the time to not only read your work but also to respond to it. It would have been easier for that person to simply take a quick glance (if at all) and say, “Looks good!” That’s not the case with your work. Your friend really wanted to try and help - which bring me to an important point. No one in their right mind spends time critiquing another person’s work unless they have the best intentions. Think about that. Would you critique their work with the goal of hurting their feelings? It’s more likely that you saw flaws and wanted to point them out.

Now that we understand the critique isn’t a personal attack, let’s look at what types of comments you might see and also how to interpret and react to them. I’ll use some of the remarks that I’ve received on my own work as reference (generalizing, of course). There are many more possible scenarios.

• This doesn’t make sense!“What? That do you mean it doesn’t make sense? I wrote it! I know what I’m talking about! “

And, perhaps you do. But, a comment like this (or something with the same meaning) indicates that the reader is confused. At the very least, it may be cause for you to look over your material more carefully. Often times, confusion is created when a critical element or detail is missing. Perhaps you thought you included the color of the murderer’s dress but in reality missed it. Did the rusty, broken-down car suddenly sparkle in the sun when it shouldn’t have? Was north by that big pine tree in one paragraph and then in the direction of the bolder 200 feet away in the next? Look for clues as to WHY the reader doesn’t understand. That may give you insight as to what is missing.

• The sentence is too long, short, or confusing.

There’s something to be said for style, here. If it’s confusing or doesn’t make sense, look for reasons why the reader doesn’t understand. If the sentence is too short or too long, perhaps it’s worth considering revision, perhaps not. Look at the pacing and rhythm of the sentences. Try reading them aloud (into a recorder if needed) to see how they flow. Imagine the work being read as an audio book. Would it work “as-is” or does it need tweaking?

• Wouldn’t he do this instead?

“It’s my character. I’ll make him do what I want!”

Amazingly, readers have a keen eye for finding lines of dialog and actions that are out of character. As a writer, it is easy (especially late in a story) to mentally merge character traits together. This is in part because we stare at them for so long within our own minds. Readers have the uncanny ability to find these discrepancies, in part, because their only window into the character’s personality is what you’ve provided. If the wallflower suddenly springs to life at the homecoming dance, there should be a good reason. Likewise, if a character sounds uncharacteristically smarter, dumber, or arrogant or if they do something that seems out of their nature, a reader will find it. Take a look. Did you really mean to do that or was it simply a slip of the pen?

• The shift from thought/situation X to Y is too fast/slow.

This is, again, a great opportunity to read the passage out loud. How does it sound? Might the reader be on to something? Should you change the pace, or is there a particular reason why you want it that way?

• I know you mean X, but it looks like your saying Y.

I get this one allot, personally. It’s usually one of my favorites because it means I’ve got the right idea, but the wrong words (or more often the wrong word order). Consider rewriting the sentence or paragraph in a different way that clarifies what you intended. This is again an example where some readers (not necessarily your critique buddy) might get confused. The comment is meant to help you sort it out before it gets into the hands of a less well-trained eye.

• Maybe you should add this piece of information I’m providing into your story.

“Who died and made you the writer? Who’s the author here? If I wanted the story like that I would have written it that way!”

Slow down - take a breath. OK, now reread what your friend wrote. Does the suggestion have merit? Do you see why she gave you that comment? What would happen if you took the suggestion and added the information/event/situation? Does the story collapse or does the suggestion make it stronger? Is there a reason to not add the information? I find this all the time, myself. For example, in one scene of my book, a group of limitary cadets is gathered in the mess hall. Their newly appointed commander bursts through the door and, the cadets quickly rush into formation: boots sparkling a glossy black with their burgundy berets tightly seated on their heads. Sounds great right? OOPS!! My critique friend pointed out that the cadets were indoors. Military tradition typically says headwear comes off to show respect when indoors. So, is this something I need to change or leave as-is? That depends on the story, and it’s something only you can decide.

• This might sound better if you moved it somewhere else in your story.

My suggestion here is to try it and see if shifting things around makes the story stronger. What can it hurt to read a few paragraphs aloud and determine if what the reader s offering might be a better way to convey your meaning.

• What’s the purpose of this part? Could you clarify more?

As shown above, readers can be easily confused. Whose fault is that? Is it theirs for not being smart enough to understand what you meant? What nerve they have for not being able to read your mind! Seriously, though, it’s more likely a case where something doesn’t make sense because there’s something missing. It might be the motivation of a character, an object that you meant to introduce in a previous scene, or the direction of the wind. You might have intentionally mentioned a character wearing a blue cotton dress, even though it seems unimportant at that moment but will come to be staggeringly profound later on. (I think of the Wizard of Oz in this last scenario.) Consider what you can do to either make the writing more concise and clear, rewording to make the flow better, add or subtract details as needed, or any other adjustment that might be needed to ensure there is no doubt in the reader’s mind about what you are trying to say.

All that to say this:

You have a great story!! What your readers want is a way to understand it. If they do not, then we can’t blame them. We can only blame ourselves. Writing is a skill that takes time to hone. Take what time you need to make it the best it can possibly be, and use your critiques as a stepping stone to greatness.

“The most successful men in the end are those whose success is the result of steady accretion... It is the man who carefully advances step by step, with his mind becoming wider and wider - and progressively better able to grasp any theme or situation - persevering in what he knows to be practical, and concentrating his thought upon it, who is bound to succeed in the greatest degree.” - Alexander Gramm Bell